All of the designers at GDS can code or are learning to code. If you’re a designer who has used prototyping tools like Axure for a large part of your professional career, the idea of prototyping in code might be intimidating. Terrifying, even.

I’m a good example of that. When I joined GDS I felt intimidated by the idea of using Terminal and things like Git and GitHub, and just the perceived slowness of coding in HTML.

At first I felt my workflow had slowed down significantly, but the reason for that was the learning curve involved – I soon adapted and got much faster.

GDS has lots of tools (design patterns, code snippets, front-end toolkit) to speed things up. Sharing what I learned in the process felt like a good idea to help new designers get to grips with how we work.

A sketch for the Highway Code

Don't be scared. First, it’s hugely helpful for new designers to understand the rationale behind why we prototype in code, and to learn some shortcuts for getting started.

HTML prototypes look very close to the real GOV.UK. They tend to be higher-quality than those produced using other prototyping tools. This is good for several reasons:

- user research participants are less likely to be distracted by visual fidelity

- it’s easy to share (no plugin required to view a web page, unlike Axure)

- the prototype works exactly like a web page. It looks and behaves like the real thing.

This post explains the original rationale for why we work this way.

A prototype does not mean code must be perfect. In fact, it shouldn’t be: the majority of time should be spent iterating the design, not making code beautiful. Prototypes are made to be tested and iterated (and if they fail, thrown away).

So it’s better if we can prototype fast. Once the design has been tested and is ready to go to production, front-end developers are there to make code efficient and secure, and to focus on things like performance.

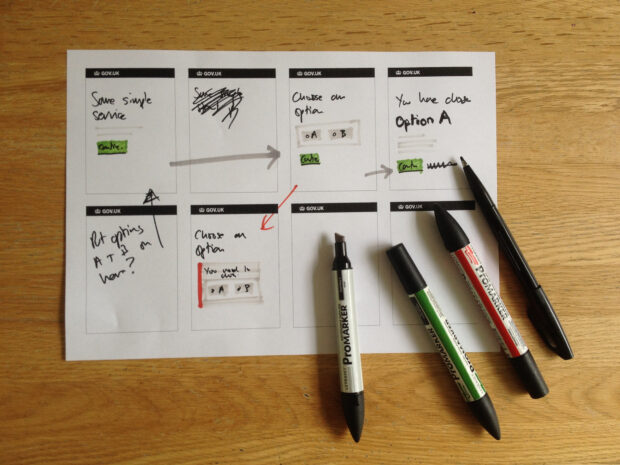

Every project and design process is different. GDS isn’t prescriptive about what you use to validate design ideas.

A design process could be anything: it might begin with sketching on paper, or mocking up using graphics software (such as Sketch or Illustrator), or downloading a GOV.UK page to edit the content locally. Or just using the browser DOM inspector to see how changing something might look.

This is how we work at GDS, and these are some of the tools we use. None of this is revolutionary. As we’ve said before, we’re flexible and optimise our approach for meeting user needs and for delivery. But here’s how we work right now.

Start with sketching

It’s always quicker to work out ideas on paper than to jump into code. Sketching is non-committal and an important part of a good design process. For sketching, all you need is some paper and good pens. Also see Ben Terrett’s sketching templates which can help you get started.

HTML and CSS

If you’re a designer with minimal HTML and CSS knowledge, it’s best to focus on getting your code working locally on a prototype kit. Once you’ve got your head around things – namely, running your prototype on a local server and using the front-end toolkit – you can move on to learning your way around Git and GitHub.

If you’re completely new to writing HTML and CSS, learn or revisit the basics on Codeacademy.

Once the prototype kit is set up, the majority of your coding at first is likely to be basic typography, so it’ll be useful to become familiar with the typographic styles on GOV.UK.

Prototype kits

Get set up with a prototype kit. A prototype kit is a set of tools that allows us to bring in GOV.UK styles, templating features, and server-side capabilities. It speeds up the prototyping process. Schedule time with a front-end developer who can help you get set up using a kit.

There are two kits (actually, there are more than two, but start with these) which are good for different things – if you’re not sure, ask to figure out what would work best for your project:

GOV.UK Prototype Kit

Good for rich, interactive prototypes, especially for designing transactions (for example). It’s worth noting that there’s a steep learning curve.

Static Prototype Kit

Good for very simple, static pages. This is a more limited prototyping kit.

Git and GitHub basics

GDS codes in the open. Even designers. GitHub which is a website where code is hosted and managed, with changes attributable to individuals. At GDS, everything possible to share is hosted on GitHub.

Git is a distributed revision control and source code management system. Don’t worry, you don’t need to know what that means.

The main benefit of using Git and GitHub is that every change (“commit”) is tracked and can be rolled back. No more FINAL_FINAL_FINAL_10_ACTUALFINAL.psds. Additionally, multiple people can contribute to a single prototype.

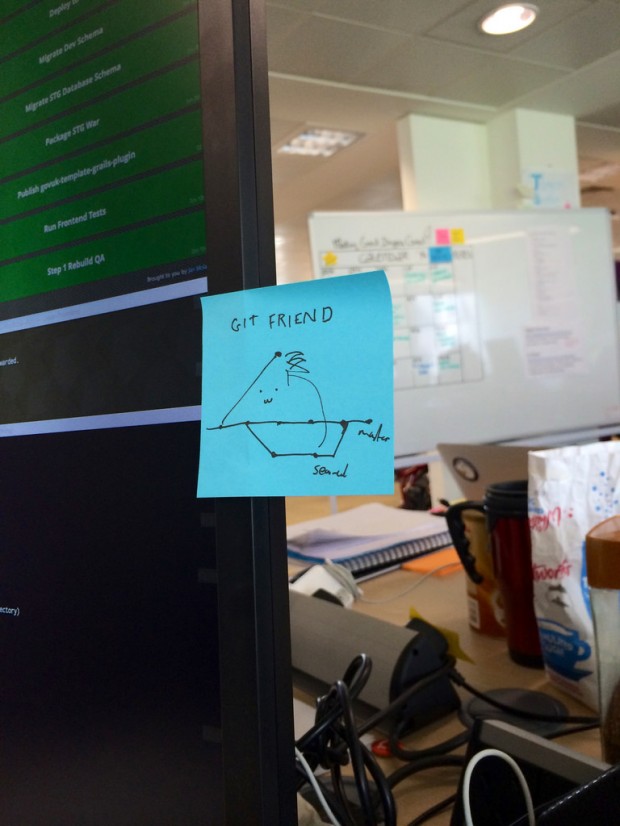

A friend's attempt to explain branching

Learning Git

There are lots of guides to Git.

Branching is a word that will come up when you read about Git. Branching is extremely useful and allows you to manage different versions of something within the same prototype. However, if you’re brand new to Git, don’t worry about the details of branching just yet, but for now think of it as a means of managing different versions of a prototype.

Hosting and sharing prototypes

You can share prototypes by hosting them on Heroku. The URL to your prototype can easily be shared and anyone can view it without having to install a plugin, because it's a website.

Here’s a guide to deploying a prototype to Heroku.

Consider whether password protecting your prototypes would be a good idea (and if in doubt, check).

Behaviour

Designers who have used prototyping tools will be familiar with tools for adding interactivity: for example, the ability to toggle a panel visibility when a button is clicked. This can done in jQuery using the same logic.

If you’ve been happy using conditional logic in prototyping software like Axure, jQuery can be used with relative ease, and the ceiling for learning is much higher. This is a good thing. The jQuery API documentation has many code examples you can use and modify, and Codeacademy has a JavaScript track.

Organising and managing versions of prototypes

If your prototype contains a lot of pages, it might be a good idea to create a contents page on the root index so your team can use it to find designs easily.

It might make sense to maintain copies of a prototype. For example, a stable version for build (rarely updated) and an experimental version for testing (constantly updated). Different prototype versions can be hosted and shared on Heroku.

A challenge is defining when a design migrates from an experimental version to a stable version that will be built, especially if you’re working on a bigger project. If you choose to work like this, make sure the process is defined well with your team.

Resources

- What's the design process at GDS?

- Useful links for new designers

- Using prototypes in user research

- Design patterns – the canonical reference for design patterns in the Service Design Manual

- Elements – a resource for pre-defined things (such as colours)

- Snippets– copy and paste into your prototype

- Design patterns hackpad – the lab for new design pattern discussion

- The Front-end toolkit – the source for styles on GOV.UK, which is used by the prototype kits

I’m Rebecca, Interaction Designer at GDS. You can follow me on twitter @rivalee

12 comments

Comment by Chris Collingridge posted on

Minor point which in no way invalidates your article: you don't need a plugin to view prototypes generated by Axure.

Comment by Rebecca Cottrell posted on

Hi Chris: sharing via AxShare doesn't require a plugin, but viewing them locally does.

Comment by Steve posted on

This is true for Chrome, but not for other browsers

Comment by Phil Gyford posted on

Thanks for writing this - I'm fascinated by the idea of designers who design in code, because I've never yet met one, much as I'd like to.

Your description does (understandably) seem very GDS-specific, and I wonder how this could work for designers in other types of organisation. For example, your designers have the benefits of an established set of design guidelines, a set of pre-defined HTML/CSS elements, and an environment in which taking the time to learn these skills is encouraged.

At the other extreme, a designer working in an agency will often find themselves designing new sites and services from scratch - so there are no design guidelines and no pre-defined elements. They will also usually have very tight deadlines and little time to stumble around with a completely new way of doing things. Which seems like a very different situation to designers at GDS.

Most of the designers I've worked with use Illustrator or Photoshop and, if they have any HTML/CSS/JS skills, they're probably 10+ years out of date. Even if they want to change how they work it must be a huge struggle and time sink - like having to suddenly write everything in a foreign language.

None of which is to detract from what you've said, which is great. It's just that I would love to know how designers outside GDS have managed this, although I expect that's outside the scope of this blog.

One thing that might be within scope is something about this topic from the point of view of a developer - How have developers helped designers get up to speed with development? What about this process is easier or harder than the "old" way of interpreting PSDs? What kind of work is involved in making a designer's (HTML) designs into production-ready code?

Comment by Chris Heathcote posted on

Hi Phil

We're just documenting what works for us - including several designers (like Rebecca) that have come from other environments, including agencies.

It's a very quick process if you have templates and example pages there already - that's true. One way to kickstart that if you have nothing is for a developer to pair with a designer. The pair should be able to create one or two base templates to throw a flow into quite quickly.

Also, for most services and transactions, working on the visual design (much) later in the process can help - it lets designers concentrate on what the page is meant to be doing and getting the words and interactions right. The fact it's a web page in a web browser means you can get good quick research feedback from people, whether or not it has the right branding.

In terms of turning it into production code - quite often the designers will be cutting and pasting code snippets into their prototypes (even someone with 10 year old HTML skills like me can do that). It will be dirty. That doesn't matter; it's meant to be thrown away. As long as a front end developer can see what the designer means (and normally working with the designer), they should have little problem re-implementing it as production-ready code. One big advantage is that there's nothing in the prototype that's hard or impossible in HTML, unlike PS/Illustrator mockups.

Comment by Geoff Delobel posted on

Thank you for sharing your process, we have a very similar one here at Central.

I was wondering if you later use the prototype code base as a start for visual design and later for development, or it's just thrown away and recoded clean from scratch with "final" design?

Also, this process works well when designing new products or services. But we are still exploring for the right process when you are adding or refining a feature for an existing product… We have tried to prototype on the existing product code, but then designers feel limited due to complex technical things to manage. We also tried to reproduce partially the product in prototype, but we then feel we are missing the whole experience, especially if the new feature also impact other parts of the product. I'm curious to know if you experimented the same issue or how you manage this?

Comment by Joe Lanman posted on

Hi – I'm also on the Design team at GDS.

We do use the prototypes for visual design, sometimes with some tweaks as it goes into production. We don't use any code directly from design prototypes, and that's an important point I think. Design prototypes should be focused on fast iteration, and shouldn't require a high level of front end skill (this means that prototyping is accessible to more designers). This means that prototype code should never be relied upon to be production ready (accessible, secure, performant etc)

It's a great point about the process being different for working on existing products, and the difficulties involved. Personally I haven't worked on too many projects like that recently, when I have I normally start with making small changes in the browser (Chrome developer tools), but larger changes I have reproduced the interface in prototype code.

Another technique I've used to prototype changes to live sites is to write a Chrome extension. You can manipulate HTML, CSS and JS on the page, and inject new code. You can use localStorage for persistence. It's a powerful technique that can really convey how changes might work on a live service.

Comment by Simon posted on

Hello,

Can somebody clear up a question I have regarding 'Designers' which seems to used a lot on this blog. What type of 'Designer' are we talking about here? User Experience Designer, Interaction Designer or Visual Designer, because in my mind there are clear job roles and distinctions between the three roles which isn't clearly explained. The term 'Designer' seems to be banded around quite a lot in a generic context. For example there is little mention of how the 'Visual Designer Process' works at GDS i.e visual design direction, choosing the colour palettes, use of colour, layout, typography, iconography etc. How does the Visual/Graphic Designer inputs into the GDS design process?

Comment by Ben Terrett posted on

Good question. We're going to cover this in a post in a week or two. Broadly speaking we mean Interaction Designers, but this also applies to Graphic (visual) Designers and Service Designers.

Comment by Simon posted on

It would be useful to update the Transactional Prototype Kit link to the active github

https://github.com/alphagov/govuk_prototype_kit

Comment by Rebecca Cottrell posted on

Thanks for the prompt – I've just updated this.

Comment by Stuart Hopper posted on

I'm working in government now as an interaction designer. Personally, having worked with code extensively as a front end dev and now being a UXer using Axure, my preference is with the latter. For me it's a no-brainer.

Prototyping in code is fine if you're doing a flat website but expecting a designer to start creating conditional logic to facilitate complex interaction in HTML/CSS/JS is going too far. Our front end guy goes straight into the prototyping framework when we're doing something simple, but anything more complex where we need to validate approaches with users I use Axure where I can put together several different approaches in a fraction of the time of the framework. I can iterate design when we're testing in the lab too. When we're happier we move design into the prototyping framework.

I think it's about looking at the task in hand and using the most appropriate tool but I can't imagine having to create the conditional logic I work with in code. There was a reason I gave up front end code and jQuery. It's called debugging!

BTW I love the way the visual design is abstracted from the interaction design process. I can just leave that aspect to the transition into the prototyping framework. I can just focus on the complexity.